The MYB gene family comprises one of the richest groups of transcription factors in plants. Plant MYB proteins are characterized by a highly conserved MYB DNA-binding domain. MYB proteins are classified into four major groups namely, 1R-MYB, 2R-MYB, 3R-MYB and 4R-MYB based on the number and position of MYB repeats. MYB transcription factors are involved in plant development, secondary metabolism, hormone signal transduction, disease resistance and abiotic stress tolerance. A comparative analysis of MYB family genes in rice and Arabidopsis will help reveal the evolution and function of MYB genes in plants.

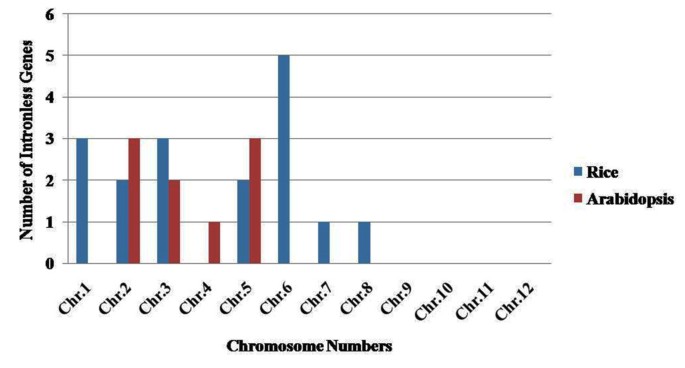

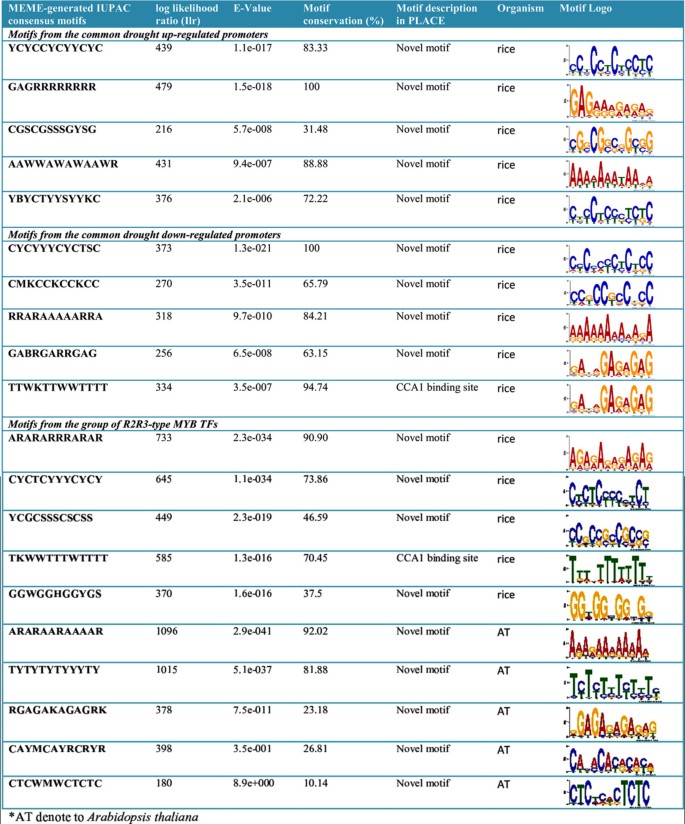

A genome-wide analysis identified at least 155 and 197 MYB genes in rice and Arabidopsis, respectively. Gene structure analysis revealed that MYB family genes possess relatively more number of introns in the middle as compared with C- and N-terminal regions of the predicted genes. Intronless MYB-genes are highly conserved both in rice and Arabidopsis. MYB genes encoding R2R3 repeat MYB proteins retained conserved gene structure with three exons and two introns, whereas genes encoding R1R2R3 repeat containing proteins consist of six exons and five introns. The splicing pattern is similar among R1R2R3 MYB genes in Arabidopsis. In contrast, variation in splicing pattern was observed among R1R2R3 MYB members of rice. Consensus motif analysis of 1kb upstream region (5′ to translation initiation codon) of MYB gene ORFs led to the identification of conserved and over-represented cis-motifs in both rice and Arabidopsis. Real-time quantitative RT-PCR analysis showed that several members of MYBs are up-regulated by various abiotic stresses both in rice and Arabidopsis.

A comprehensive genome-wide analysis of chromosomal distribution, tandem repeats and phylogenetic relationship of MYB family genes in rice and Arabidopsis suggested their evolution via duplication. Genome-wide comparative analysis of MYB genes and their expression analysis identified several MYBs with potential role in development and stress response of plants.

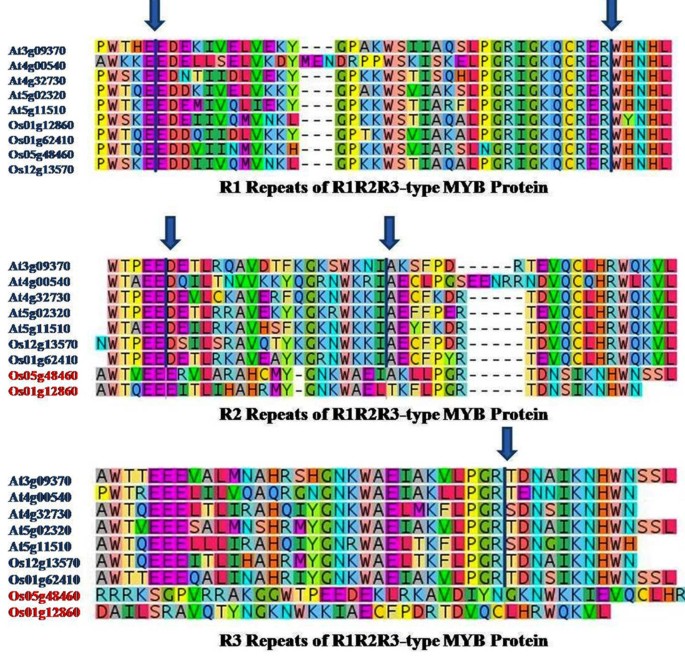

Transcription factors are essential regulators of gene transcription and usually consist of at least two domains namely a DNA-binding and an activation/repression domain, that function together to regulate the target gene expression[1]. The MYB (my elob lastosis) transcription factor family is present in all eukaryotes. "Oncogene" v MYB was the first MYB gene identified in avian myeloblastosis virus[2]. Three v MYB-related genes namely c-MYB, A-MYB and B-MYB were subsequently identified in many vertebrates and implicated in the regulation of cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis[3]. Homologous genes were also identified in insects, fungi and slime molds[4]. A homolog of mammalian c-MYB gene, Zea mays C1, involved in regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis, was the first MYB gene to be characterized in plants[5]. Interestingly, plants encode large number of MYB genes as compared to fungi and animals[6–12]. MYB proteins contain a MYB DNA-binding domain, which is approximately 52 amino acid residues in length, and forms a helix-turn-helix fold with three regularly spaced tryptophan residues[13]. The three-dimensional structure of the MYB domain showed that the DNA recognition site α-helix interacts with the major groove of DNA[14]. However, amino acid sequences outside the MYB domain are highly divergent. Based on the number of adjacent MYB repeats, MYB transcription factors are classified into four major groups, namely 1R-MYB, 2R-MYB, 3R-MYB and 4R-MYB containing one, two, three and four MYB repeats, respectively. In animals, R1R2R3-type MYB domain proteins are predominant, while in plants, the R2R3-type MYB domain proteins are more prevalent[4, 7, 15]. The plant R2R3-MYB genes probably evolved from an R1R2R3-MYB gene progenitor through loss of R1 repeat or from an R1 MYB gene through duplication of R1 repeat[16, 17].

In plants, MYB transcription factors play a key role in plant development, secondary metabolism, hormone signal transduction, disease resistance and abiotic stress tolerance[18, 19]. Several R2R3-MYB genes are involved in regulating responses to environmental stresses such as drought, salt, and cold[9, 20]. Transgenic rice over expressing OsMYB3R 2 exhibited enhanced cold tolerance as well as increased cell mitotic index[21]. Enhanced freezing stress tolerance was observed in Arabidopsis over-expressing OsMYB4[10, 22]. Arabidopsis AtMYB96, an R2R3-type MYB transcription factor, regulates drought stress response by integrating ABA and auxin signals[23]. Transgenic Arabidopsis expressing AtMYB15 exhibited hypersensitivity to exogenous ABA and improved tolerance to drought[24], and cold stress[20]. The AtMYB15 negatively regulated the expression of CBF genes and conferred freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis[20]. Other functions of MYBs include control of cellular morphogenesis, regulation of secondary metabolism, meristem formation and the cell cycle regulation[15, 25–28]. Recent studies have shown that the MYB genes are post-transcriptionally regulated by microRNAs; for instance, AtMYB33, AtMYB35, AtMYB65 and AtMYB101 genes involved in anther or pollen development are targeted by miR159 family[29, 30].

MYB TF family genes have been identified in a number of monocot and dicot plants[9], and evolutionary relationship between rice and Arabidopsis MYB proteins has been reported[31]. We report here genome-wide classification of 155 and 197 MYB TF family genes in rice and Arabidopsis, respectively. We also analysed abiotic stress responsive and tissue specific expression pattern of the selected MYB genes. To map the evolutionary relationship among MYB family members, phylogenetic trees were constructed for both rice and Arabidopsis MYB proteins. Several over- represented cis-regulatory motifs in the promoter region of the MYB genes were also identified.

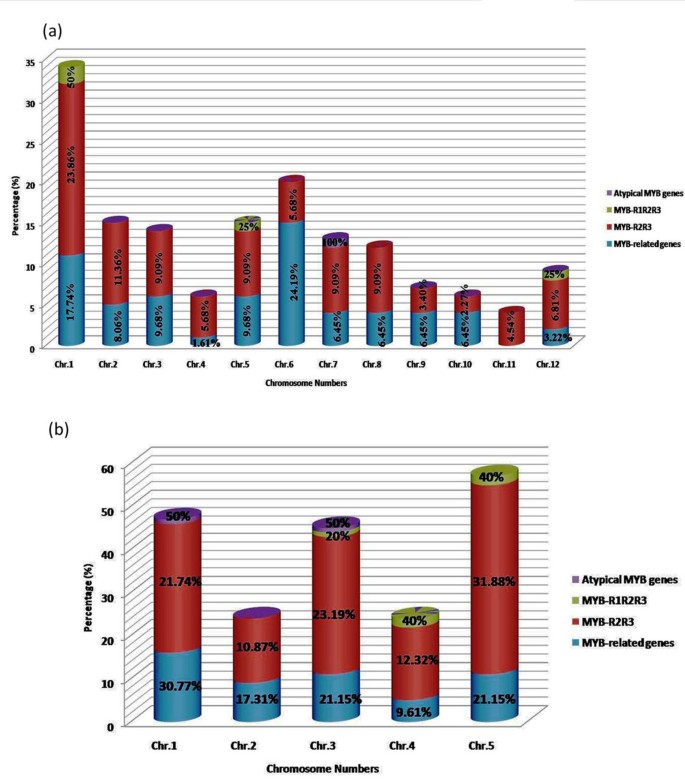

Genome-wide analysis led to the identification of 155 and 197 MYB genes in rice and Arabidopsis, respectively, with their mapping on different chromosomes (Additional file1: Table S1). We used previously assigned names to the MYB genes; for instance, AtMYB0 (GL1) name was accepted for the first identified R2R3 MYB gene; subsequently identified R2R3 MYB genes were named as AtMYB1, AtMYB2, etc. in Arabidopsis[31–34]. We classified MYB transcription factors in to four distinct groups namely “MYB-related genes”, “MYB-R2R3”, “MYB-R1R2R3”, and “Atypical MYB genes” based on the presence of one, two, three and four MYB repeats, respectively. Our analysis revealed that the MYB-R2R3 subfamily consisted of the highest number of MYB genes, with 56.77 and 70.05% of the total MYB genes in rice and Arabidopsis, respectively (Figure1a, b). In the R2R3-MYB proteins, N-terminal consists of MYB domains, while the regulatory C-terminal region is highly variable. Presence of a single MYB-like domain (e.g. hTRF1/hTRF2) in their C terminus is required for telomeric DNA binding in vitro[35]. Earlier study revealed that the R2R3-MYB related proteins arose after loss of the sequences encoding R1 in an ancestral 3R-MYB gene during plant evolution[36]. In contrast, only few MYB-R1R2R3 genes were identified in Arabidopsis and rice with 5 and 4 genes, respectively. The category “MYB-related genes” usually but not always contain a single MYB domain[17, 31, 36]. We found that “MYB-related genes” represented 40 and 26.39% of the total MYB genes in rice and Arabidopsis, respectively (Figure1a, b), and thus constituted the second largest group of MYB proteins in both rice and Arabidopsis. We also identified one MYB protein in rice and two MYB proteins in Arabidopsis that contained more than three MYB repeats and these belong to “Atypical MYB genes” group. The AT1G09770 in Arabidopsis and LOC_Os07g04700 in rice have five MYB domains and are called as CDC5-type protein, whereas AT3G18100 of Arabidopsis has four MYB domains and is named as 4R-type MYB (Table1; Additional file1: Table S1). The 4R-MYB proteins belong to the smallest class, which contains R1/R2-like repeats. MYB genes can also be classified into several subgroups based on gene function, such as Circadian Clock Associated1 (CCA1) and Late Elongated Hypocotyl (LHY), Triptychon (TRY) and Caprice (CPC)[15, 17, 37]. CPC and TRY belong to the R3-MYB group and are mainly involved in epidermal cell differentiation, together with ENHANCER OF TRY AND CPC1, 2 and 3 (ETC1, ETC2 and ETC3), and TRICHOMELESS1 and 2 (TCL1 and TCL2)[38–41]. Here, we observed that CCA1, CPC and LHY subgroups contain 23, 3 and 1 ‘MYB-related’ TF, respectively in Arabidopsis. To further understand the nature of MYB proteins, their physiochemical properties were also analyzed. The MYB proteins have similar grand average hydropathy (GRAVY) scores. Kyte and Doolittle[42] proposed that higher average hydropathy score of a protein indicates physiochemical property of an integral membrane protein, while a negative score indicates soluble nature of the protein. We observed that all MYB proteins in rice and Arabidopsis, except AT1G35516 had a negative GRAVY score, suggesting that MYBs are soluble proteins, a character that is necessary for transcription factors. Minimum and maximum score of GRAVY were recorded as −1.287 (LOC_Os02g47744) and −0.178 (LOC_Os08g37970) in rice, and −1.359 (AT5G41020) and 0.612 (AT1G35516) in Arabidopsis, respectively. We also calculated average isoelectric point (pI) value. The mean pI values for MYB-1R, R2R3 and R1R2R3 protein families were 7.55, 6.90 and 7.25 in rice, and 7.55, 6.89 and 6.80 in Arabidopsis, respectively. The average molecular weight of MYB-1R, R2R3 and R1R2R3 protein families were 31.128, 34.561 and 72.52 kDa in rice, and 34.186, 35.875 and 86.217 kDa in Arabidopsis, respectively (Additional file1: Table S1).

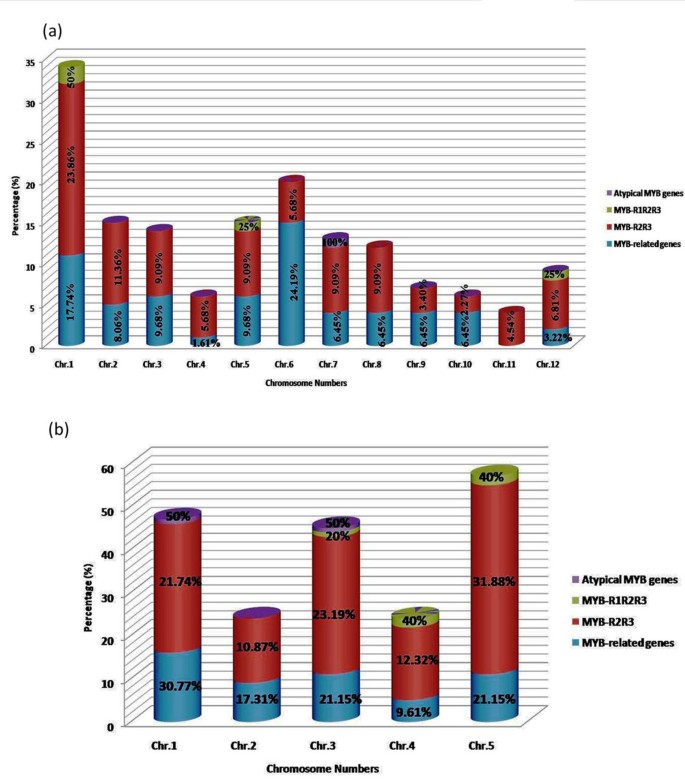

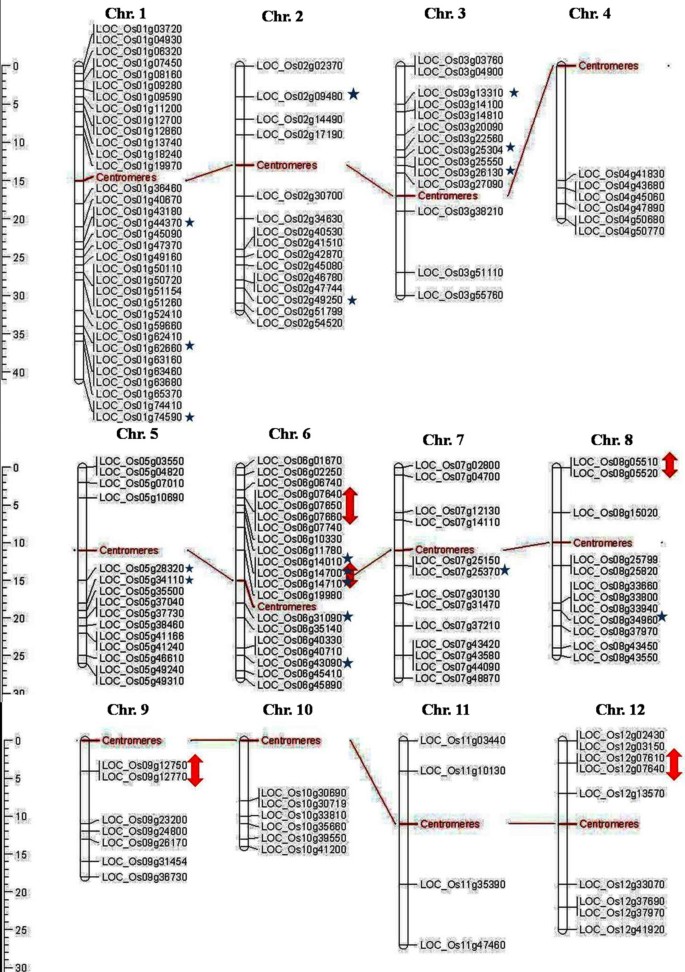

The position of all 155 OsMYB and 197 AtMYB genes were mapped on chromosome pseudomolecules available at MSU (release 5) for rice and TAIR (release 8) for Arabidopsis (Figures5 and6). The distribution and density of the MYB genes on chromosomes were not uniform. Some chromosomes and chromosomal regions have high density of the MYB genes than other regions. Rice chromosome 1 and Arabidopsis chromosome 5 contained highest density of MYB genes, i.e. 21.93 and 28.93%, respectively. Conversely, chromosome 11 of rice and chromosome 2 of Arabidopsis contained lowest density of MYB genes, i.e. 2.58 and 12.69%, respectively. Distribution of MYB genes on chromosomes revealed that lower arm of chromosomes are rich in MYB genes, i.e. 65.16% in rice and 52.79% in Arabidopsis. Distribution pattern also revealed that chromosome 5 in rice, and chromosome 2 and 5 in Arabidopsis contained higher number of MYB genes with introns, i.e. 29.41 and 33.33%, respectively. Intronless MYB genes are absent in chromosome 4, 9, 10, 11 and 12 in rice, and chromosome 1 in Arabidopsis (Figure2). Distribution of MYB genes on chromosomal loci revealed that 11 (7.09%) in rice and 20 (10.15%) genes in Arabidopsis were found in tandem repeats suggesting local duplication (Table2). Chromosome 6 in rice and chromosome 1 in Arabidopsis contained higher number of tandem repeats, i.e. 7 genes and showed over-representation of MYB genes. Three direct tandem repeats were found on chromosome 6 (LOC_Os06g07640; LOC_Os06g07650; LOC_Os06g07660) in rice, and chromosome 1 (AT1G66370, AT1G66380; AT1G66390) as well as chromosome 5 (AT5G40330; AT5G40350; AT5G40360) in Arabidopsis. Four direct tandem repeats were also observed on chromosome 3 (AT3G10580, AT3G10585, AT3G10590 and AT3G10595) in Arabidopsis. Manual inspection unraveled 44 (28.38 %) and 69 (35.02%) homologous pairs of MYB genes in rice and Arabidopsis, respectively evolved due to segmental duplication. We also observed that two homologous pairs in Arabidopsis contained one MYB gene and other than that was not classified as MYB gene in TAIR (release 10) databases (Table3). About 44 (28.39%) OsMYB and 69 (35.02%) AtMYB genes showed homology with multiple genes including MYB genes from various locations on different chromosomes. It is widely accepted that redundant duplicated genes will be lost from the genome due to random mutation and loss of function, except when neo-or sub-functionalization occur[60, 61]. Rabinowicz et al. (1999) suggested that gene duplications in R2R3-type MYB family occurred during earlier period of evolution in land plants[62]. Recently, a range of duplicated pair of MYB genes in R2R3-type protein family has been identified in maize[63]. Among the tandem repeat pair (AT2G26950 and AT2G26960) in Arabidopsis, AtMYB104 (AT2G26950) is down-regulated by ABA, anoxia and cold stress, but up-regulated under drought, high temperature and salt, while AtMYB81 (AT2G26960) expression pattern was opposite to that of AtMYB104, i.e., AtMYB81 is up-regulated in response to ABA, anoxia and cold stress, but down regulated under drought, high temperature and salt stresses. Similar diversification was also observed in the duplicate pair (LOC_Os10g33810 and LOC_Os02g41510) in rice. OsMYB15 (LOC_Os10g33810) expressed in leaf, while LOC_Os02g41510 expressed in shoot and panicle tissue. These spatial and temporal differences among different MYB genes evolved by duplication indicate their functional diversification.

To identify MYB genes with a potential role in abiotic stress response of plants, we analyzed the expression pattern of MYB genes in response to abiotic stresses. Expression of MYBs genes was examined from the availability of full-length cDNA (FL-cDNA) and Expressed Sequence Tag (EST) available at MSU and dbEST databases for rice and Arabidopsis, respectively[68]. It was found that 109 OsMYB genes in rice and 157 AtMYB genes in Arabidopsis had one or more representative ESTs. The LOC_Os10g41200 and AT5G47390 gene in rice and Arabidopsis had maximum number of ESTs, that is, 219 and 44, respectively. About 70% of rice MYB genes and 80% of Arabidopsis MYB genes appeared to be highly expressed as evident from the availability of ESTs for these genes (Additional file6: Table S6). Further, we assessed the expression levels of MYB genes under various abiotic stresses by PlantQTL-GE[69], GENEVESTIGATOR[70, 71] and our previous microarray data experiment (E-MEXP-2401) with rice cv. Nagina 22 and IR64 under normal and drought conditions (Additional file7: Table S7). In our previous microarray data experiments, we found that 142 (92.26%) MYB genes were expressed in seedlings of rice (Additional file8: Figure S1), of which 92 genes were differentially regulated under drought stress. In IR64, 30 genes were up-regulated (≥ 2.0 fold) and 30 genes were down-regulated (≤ 2.0 fold), while in Nagina 22, 22 genes were up-regulated (≥ 2.0 fold) and 19 genes were down-regulated (≤ 2.0 fold) under drought stress. The exploration of PlantQTL-GE for rice MYBs showed that 14 (9.03%) OsMYB genes were up-regulated under cold, drought and salt stress in rice, of which 10 are up-regulated under drought condition. These results suggest that large set of MYB genes may have a role in drought stress response in rice. Previous studies have shown that over-expression of MYB genes improved abiotic stress tolerance of rice and Arabidopsis[24, 72]. In addition to these, we have identified additional MYB genes that are regulated by drought and other stresses, and thus can be used as candidate genes for functional validation. The GENEVESTIGATOR analysis showed that 44.67, 41.12 and 56.85% AtMYB genes were down regulated and 47.21, 50.76 and 35.02% AtMYB genes were up regulated in cold, drought and salt stress, respectively (Additional file9: Figure S2a, b and c, Additional file10: Figure S3).

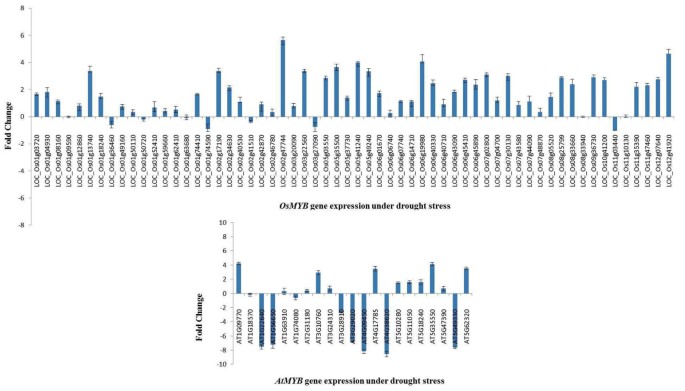

We analyzed expression patterns of 60 OsMYB and 21 AtMYB genes using QRT-PCR. These genes were selected based on phylogenetic analysis and one gene from each cluster was selected for expression analysis. Out of the 60 genes examined by QRT-PCR, 28 OsMYB genes were up-regulated (≥ 1.5 fold change) under drought stress in rice cv. Nagina 22 (Figure8). We also found that LOC_Os02g47744, LOC_Os12g41920 and LOC_Os06g19980 were highly up-regulated (≥ 4 fold change), indicating their potential role in drought stress. QRT-PCR analysis of 21 MYB genes in Arabidopsis revealed that 7 AtMYB genes were up-regulated (≥ 1.5 fold changes) and another 7 AtMYB genes were down-regulated (≤ 1.5 fold change) under drought stress (Figure8).

In rice, a tissue breakdown of EST evidence for MYB genes was analyzed using the Rice Gene Expression Anatomy Viewer, MSU database[73, 74]. In case of Arabidopsis, tissue-specific expressions of MYB genes were obtained from GENEVESTIGATOR tool[70, 71]. The expression patterns of MYB genes in different tissues are listed in Additional file11: Table S8. The results showed that large numbers of OsMYB genes (32.90%) were highly expressed in the panicle, leaf and shoots (Additional file12: Figure S4). EST frequency analysis suggested that OsMYB g enes, LOC_Os02g34630, LOC_Os08g05510, LOC_Os01g74590, LOC_Os02g09480, LOC_Os09g36730, OsMYB4, LOC_Os10g41200 and LOC_Os01g13740 are highly expressed in flower, anther, endosperm, pistil, shoot, panicle, immature seed and whole plant, respectively. In case of leaves, we observed that three MYB genes, i.e., OsMYB48, LOC_Os06g40710 and LOC_Os10g41200 showed highest levels of expression. In Arabidopsis, the following MYB genes expressed at a very high level: AtMYBCDC5 in callus and seed; AT1G19000 in seedling and stem; AT1G74840 in root and root tip; AT1G26580 in flower, AtMYB91 in shoot, and AtMYB44 in pedicel and leaves. In wheat, TaMYB1 showed high expression in root, sheath and leaf, while TaMYB2 expression was highest in root and leaf, but at low in sheath[75]. TaMYB1 and TaMYB2 showed a very high sequence similarity with AtMYB44 and OsMYB48, respectively. Our analysis also revealed that these two MYBs are highly expressed in leaf as in case of wheat. These analyses will be useful in selecting candidate genes for functional analysis of their role in a specific tissue.

To understand the evolutionary relationship among MYB family genes, phylogenetic trees were constructed using the multiple sequence alignment of MYB proteins[76]. The tree revealed that tandem repeat and homologous pairs were grouped together into single clade with very strong bootstrap support (Additional file13: Figure S5). These results further support gene duplication in rice and Arabidopsis during evolution which may allow functional diversification by adaptive protein structures[77]. It was also noticed that few “homologues pairs” (e.g. AT5G16600-AT3G02940 in Arabidopsis; LOC_Os12g07610- LOC_Os12g07640 in rice) and “tandem repeat pairs” (e.g. AT3G12720-AT3G12730 in Arabidopsis; LOC_Os06g14700-LOC_Os06g14710 in rice) were found in distinct clade, indicating that only few members had common ancestral origin that existed before the divergence of monocot and dicot. MYB proteins from rice and Arabidopsis with same number of MYB domains were grouped into a single clade. For instance, all the MYBs belonging to R1R2R3 family in both rice and Arabidopsis were clustered into single clade. Within the R2R3 clade, MYBs from rice and Arabidopsis were not found in distinct groups. These results suggest that significant expansion of R2R3-type MYB genes in plants occurred before the divergence of monocots and dicots, which in agreement with the previous studies[4, 62]. Finally, we observed that two CDC5-type and one 4-repeat MYB orthologs were clustered into single clade and might have been derived from an ancient paralog of widely distributed R2R3 MYB genes.

Our study provides genome-wide comparative analysis of MYB TF family gene organization, sequence diversity and expression pattern in rice and Arabidopsis. Structural analysis revealed that introns are highly conserved in the central region of the gene, and R2R3-type MYB proteins usually have two introns at conserved positions. Analysis of length and splicing of the intron/exon and their position in MYB domain suggested that introns were highly conserved within the same subfamily. Most of the MYB genes are present as duplicate genes in both rice and Arabidopsis. Phylogenetic analysis of rice and Arabidopsis MYB proteins showed that tandem repeat and homologous pair was grouped together into single clade. Consensus motif analysis of 1kb upstream region of MYB gene ORFs led to the identification of conserved and over-represented cis-motifs in both rice and Arabidopsis. The comparative analysis of MYB genes in rice and Arabidopsis elucidated chromosomal location, gene structure and phylogenetic relationships, and expression analysis led to the identification of abiotic stress responsive and tissue-specific expression pattern of the selected MYB genes, suggesting functional diversification. Our comprehensive analyses will help design experiments for functional validation of their precise role in plant development and stress responses.

To identify MYB transcription factor family genes, we searched and obtained genes annotated as MYB in MSU (release 5) for rice and TAIR (release 8) for Arabidopsis by using in-house PERL script along with careful manual inspection. The primary search disclosed 161 and 199 members annotated as “MYB” or “MYB-related genes” in MSU and TAIR database, respectively. We observed that some protein members lack MYB-DNA binding domain but still annotated as MYB protein family in MSU and TAIR database. We discarded these proteins based in the annotation in MSU (release 7) for rice and TAIR (release 10). Finally, we obtained 155 and 197 MYB genes in rice and Arabidopsis, respectively. The gene identifiers were assigned to each OsMYB and AtMYB genes to avoid confusion when multiple names are used for same gene. Uncharacterized MYB genes are denoted here by their locus id.

To identify number of domains present in MYB protein we executed domain search by Conserved Domains Database[78] (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/cdd.shtml) and pfam database[79] (http://pfam.sanger.ac.uk/)with both local and global search strategy and expectation cut off (E value) 1.0 was set as the threshold for significance. Only significant domain found in rice and Arabidopsis MYB protein sequence were considered as a valid domain. To get more information about nature of the MYB protein, grand average of hydropathy (GRAVY), PI and the molecular weight were predicted by ProtParam tool available on Expert Protein Analysis System (ExPASy) proteomics server (http://www.expasy.ch/tools/protparam.html). The subcellular localization of MYB proteins were predicted by Protein Localization Server (PLOC) (http://www.genome.jp/SIT/plocdir/), Subcellular Localization Prediction of Eukaryotic Proteins (SubLoc V 1.0) (http://www.bioinfo.tsinghua.edu.cn/SubLoc/eu_predict.htm), SVM based server ESLpred (http://www.imtech.res.in/raghava/eslpred/submit.html), and ProtComp 9.0 server (http://linux1.softberry.com/berry.phtml?topic=protcomppl&group=programs&subgroup=proloc). Further, species-specific localization prediction system was utilized for Arabidopsis (AtSubP,http://bioinfo3.noble.org/AtSubP/)[57]. MYB protein function in term of their Gene Ontology (GO) was predicted by GO annotation search page available at MSU (http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu/downloads_gad.shtml) and TAIR (http://www.arabidopsis.org/tools/bulk/go/index.jsp) for rice and Arabidopsis, respectively. Localization consensus was predicted based on majority of result. The confidence level was acquired by assigning equal numeric value (e.g. one) to each general localization predictor and higher value to gene ontology (e.g. two) and species specific predictor (e.g. three).

To generate the phylogenetic trees of MYB transcription factor family genes, multiple sequence alignment of MYB protein sequence were performed using COBALT program[82] (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/cobalt/). COBALT program automatically utilize information about bona fide proteins (i.e. MYB domains in this case) to execute multiple sequence alignment and build phylogenetic tree. The dendrogram were constructed with the following parameters; method-fast minimum evolution, max sequence difference-0.85, distance- grishin (protein).

To map the gene loci on rice and Arabidopsis chromosomes pseudomolecules were used in MapChart (version 2.2) program[83] for rice and chromosome map tool[84] for Arabidopsis available on The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR) database (http://www.arabidopsis.org/jsp/ChromosomeMap/tool.jsp). Tandem repeats were identified by manual visualization of rice and Arabidopsis physical map. Duplication or homologous pair genes were obtained by the segmental genome duplication segment (http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu/segmental_dup/) and Arabidopsis Syntenic Pairs / Annotation Viewer (http://synteny.cnr.berkeley.edu/AtCNS/) in rice (distance = 500kb) and Arabidopsis, respectively. The tandem repeat and homologous pairs were aligned with the BLAST 2 SEQUENCE tool available on National Center on Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi/).

To know more about intron / exon structure, MYB coding sequence (CDS) were aligned with their corresponding genomic sequences using spidey tool available on NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/spidey/). To identify conserved intronless genes between rice and Arabidopsis, local protein blast (BLASTP) (http://www.molbiol.ox.ac.uk/analysis_tools/BLAST/BLAST_blastall.shtml) was performed for protein sequences of all predicted intronless genes in rice against all predicted intronless gene in Arabidopsis, and vice versa. Hits with 1e-6 or less were treated as conserved intronless genes and hits with 1e-10 or less were treated as paralogs. The cutoff of sequence identity was considered as ≥ 20% over the 70% average query coverage.

Expression support for each gene model is explored through gene expression evidence search page (http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu/locus_expression_evidence.shtml) available at MSU for rice and GENEVESTIGATOR tool (https://www.genevestigator.com/) for Arabidopsis. MYB genes for which no ESTs were found, blast (BLASTP and TBLASTN) (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) search using NCBI databases was performed. Significant similarity of MYB genes with MYB genes of other plant species was searched. To measure the MYB expression level in abiotic stress plant QTLGE database was used (http://www.scbit.org/qtl2gene/new/) for rice and GENEVESTIGATOR tool (https://www.genevestigator.com/) for Arabidopsis. To identify tissue specific expression level of OsMYB genes in rice, highly expressed gene search (http://Rice.plantbiology.msu.edu/tissue.expression.shtml) available at MSU were used. For Arabidopsis, GENEVESTIGATOR tool (https://www.genevestigator.com/gv/user/gvLogin.jsp) was used.

The plant materials used were drought tolerant rice (Oryza sativa L. subsp. Indica) cv. Nagina 22 and Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Columbia. The seeds were surface sterilized. Rice seeds were placed on absorbent cotton, which was soaked overnight in water and kept in medium size plastic trays. Arabidopsis seeds were germinated on MS-agar medium containing 1% Sucrose and seven days old seedlings were transferred to soilrite for further growth. The rice and Arabidopsis seedlings were grown in a greenhouse under the photoperiod of 16/8 h light/dark cycle at 28°C ± 1 and 23°C ± 1, respectively.

Drought was imposed to 3-weeks old rice seedlings[85] and 5-week-old Arabidopsis plants by withholding water till visible leaf rolling was observed. Control plants were irrigated with sufficient water. Plant water status was quantified by measuring relative water content of leaf. Control plants showed 96.89 and 97.49% RWC (relative water content), while stressed plants showed 64.86 and 65.2% RWC in rice and Arabidopsis, respectively.

Total RNA from rice and Arabidopsis were isolated by TRIzol Reagent (Ambion) and treated with DNase (QIAGEN, GmbH). The first strand cDNA of rice and Arabidopsis was synthesized using Superscript III Kit (Invitrogen) from 1 μg of total RNA according to manufacturer’s protocol. Reverse transcription reaction was carried out at 44°C for 60 min followed by 92°C for 10 min. Five ng of cDNA was used as template in a 20 μL RT reaction mixture. Sixty three pairs of rice and 51 pairs of Arabidopsis gene specific primers were used to study expression of MYB transcription factor. Gene specific primers were designed using IDT PrimerQuest (http://www.idtdna.com/scitools/applications/primerquest/default.aspx). Ubiquitin and actin primers were used as an internal control in rice and Arabidopsis, respectively. The primer combinations used here for real-time RT-PCR analysis specifically amplified only one desired band. The dissociation curve testing was carried out for each primer pair showing only one melting temperature. The RT-PCR reactions were carried out at 95°C for 5 min followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15s and 60°C for 30s each by the method described previously by Dai et al., 2007[24]. For qRT-PCR, QuantiFast SYBR Green PCR master mix (QIAGEN GmbH) was used according to manufacturer’s instruction. The threshold cycles (CT) of each test target were averaged for triplicate reactions, and the values were normalized according to the CT of the control products (Os-actin or Ubiquitin) in case of rice and Arabidopsis, respectively. MYB TFs expression data were normalized by subtracting the mean reference gene CT value from individual CT values of corresponding target genes (ΔCT). The fold change value was calculated using the expression, where ΔΔCT represents difference between the ΔCT condition of interest and ΔCT control. The primer sets used to study the MYB TFs expression profile are given in the Additional file14: Table S9.

Michigan State University

The Arabidopsis Information Resource

Practical Extraction and Report Language

Basic Local Alignment Search Tool

Multiple Expectation Maximization for Motif Elicitation

Expressed Sequence Tag

National Center for Biotechnology Information

Gene Expression Omnibus

Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction.

We thank Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) for supporting this work through the ICAR-sponsored Network Project on Transgenics in Crops (NPTC) and National Initiative on Climate Resilient Agriculture (NICRA). SKL gratefully acknowledge University Grants Commission (UGC) and Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) for CSIR-UGC Junior and Senior Research Fellowship Grant. SS and RR acknowledge the senior research and research associate fellowship grant by Department of Biotechnology (DBT), Govt. of India, respectively. We thank Cathie Martin, John Innes Centre, Norwich Research Park, Colney, Norwich, UK, for her valuable suggestions on the data analysis and manuscript.